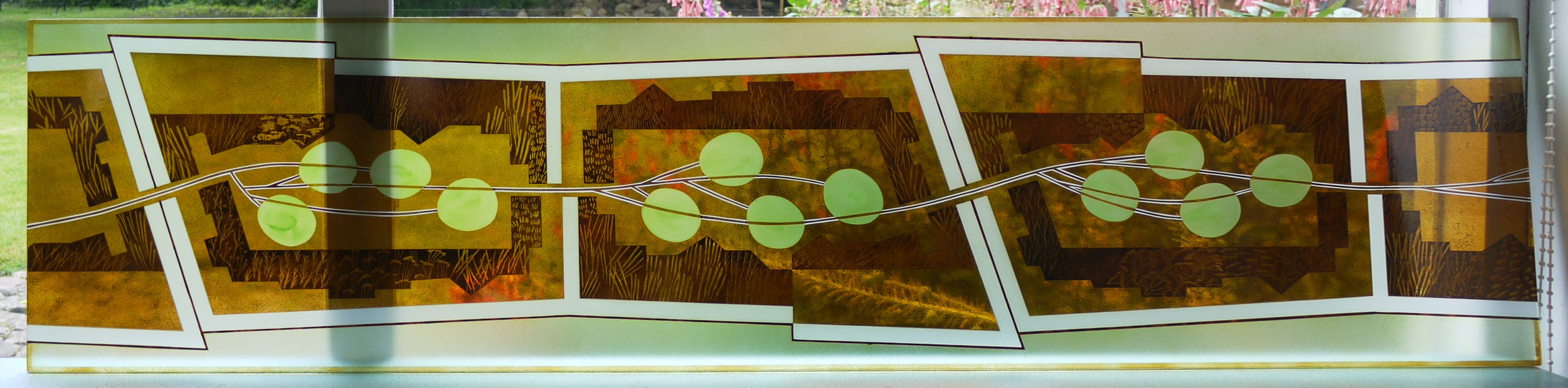

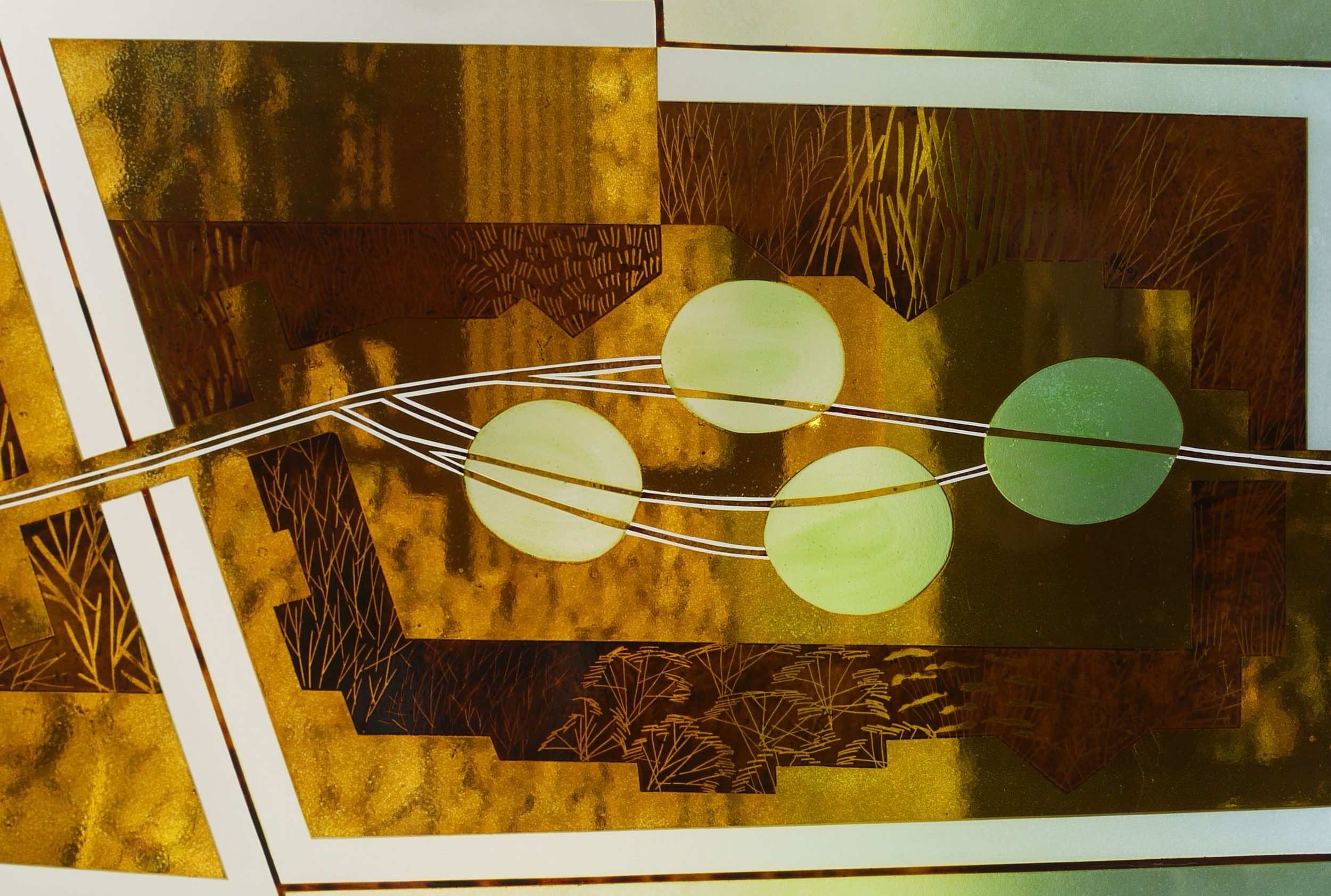

Rosalind Grimshaw window in Urchfont church, 2000.

I visited St. Michael and All Angels church in Urchfont because my excellent guidebook from Wiltshire Historic Churches Trust mentioned a millennium window there by Rosalind Grimshaw. It's a small window but really expressive with good colour and glass. The whole church is lovely and its stained glass rich and varied. The patterned windows on the south side look great from both inside and out - with columns of big satisfying circles - until you think what wonderful medieval glass might have been there originally.

Victorian patterned windows on the south side

This set us thinking about how to answer the question (of the frequently asked variety), why is medieval stained glass the best? It's too dangerous to mention the quality of the glass itself, because that leads people to believe the myth that you can't get good glass anymore, although when you look at the angel detail from the large south window you can see how harsh and brittle looking the coloured glass is in these particular Victorian windows.

Angel details from south window

Victorian angels in the chancel

Moving down into the chancel, the angels at the tops of the windows become more interesting, and older. The pair on either side of the altar (below), six winged seraphim holding crowns, are beautiful - with a captivating expression that is so obviously medieval.

Seraphim in the chancel

The information in the church describes, as usual, the stained glass as either "medieval", "victorian" or "modern", with the sub group of "imitation medieval" for the beautifully coloured patterned windows underneath the seraphim (below right). This convention of copying the medieval window style is the reason why they could never be as good as the originals. Those seraphim were made by people who believed in the work they were doing. The sincerity comes across in the expression of the figures, while the style and workmanship of the windows perfectly compliments the medieval building for which they were made.

Face of the seraph: window on north side of chancel - chancel built around 1340

Click on any of the photos to enlarge them