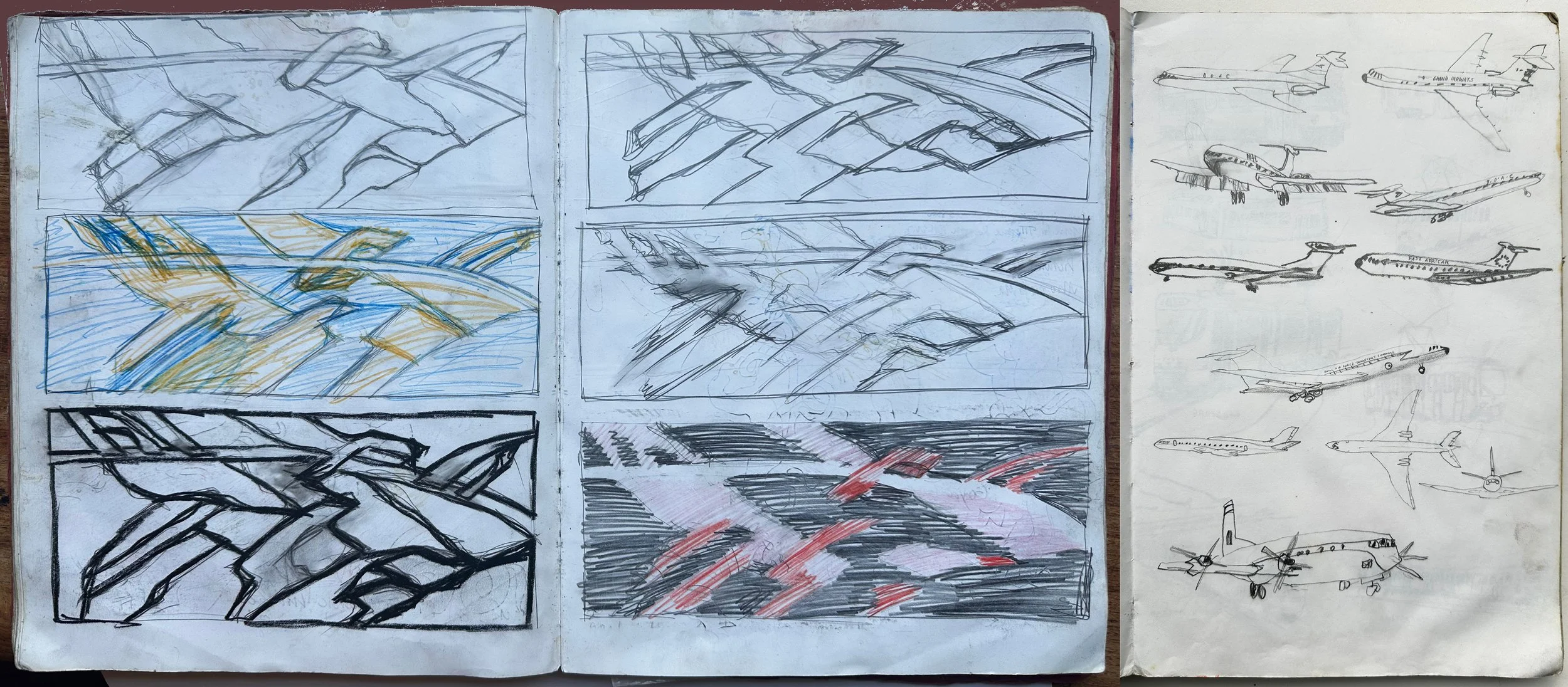

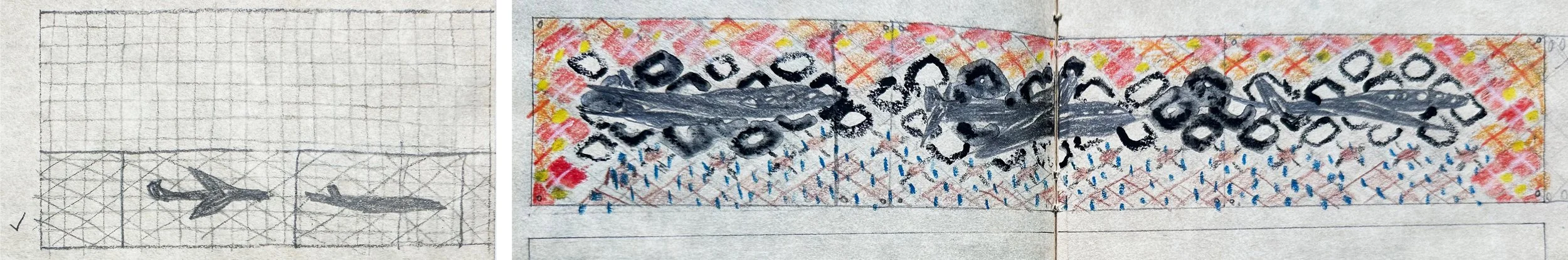

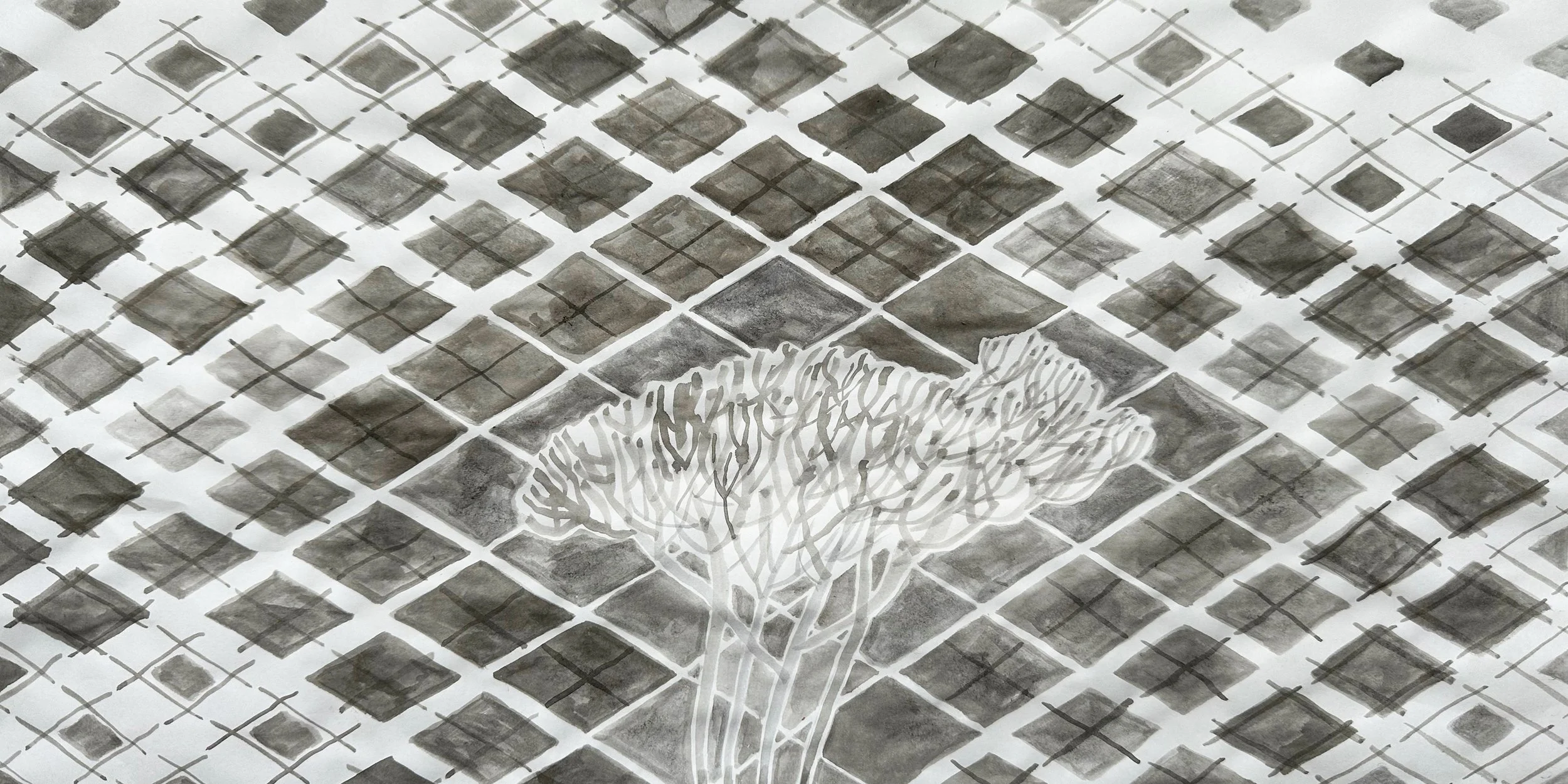

Droitwich Town mural by Philippa Threlfall and Kennedy Collings, made in 1976 and restored this year by the artist.

I’ve been to some really interesting places just because they are a stopping off point on the way to somewhere else - like Droitwich Spa, seven minutes drive from the M5 and therefore on our route up the motorway on Christmas Eve this year. In the centre is the town’s cherished mosaic mural, beautifully made by Philippa Threlfall in 1979; her work was widely commissioned for public art projects from the 1960s up to the present day. I knew there were six churches in the town and the picture of the Catholic Church with its tall exotic looking bell tower, at top right in the mural, sent us straight there.

Inside the Church of the Sacred Heart and Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Droitwich Spa, Worcestershire.

The Roman Catholic Church of of the Sacred Heart and St Catherine of Alexandria was designed (in the early Christian style) by F Barry Peacock and commissioned by Walter Loveridge Hodgkinson, it opened in 1921. There are photographs showing white walls when the church opened, now they are covered in mosaic, mostly executed from 1922 - 1932 by the experienced mosaicists Maurice Josey and Fred Oates to a design by Gabriel Pippet. These are mosaics made with glass tesserae that sparkle when you turn the lights on, their design unmistakably influenced by Pippet’s time spent in Rome and Ravenna, down to the row of beasts (supposedly hart) that trot around the curve of the apse as the sheep do in St Apollinanare, Ravenna. The lower walls are lined with grey, green and blue marble that creates a beautiful surface.

In the photos of the small side chapels (below) you can see how the gold on the back of the tesserae glows behind the Nativity scene and the mosaic of the church itself. On the north side the middle row of mosaics shows the Life of the Virgin, those on the south side illustrate the life of St Richard of Chichester (also know as Richard de Wych) who was born near Droitwich.

Left: Nativity scene in the south aisle. Right: North aisle with nativity above and mosaic image of the church below.

The Chapel of Our Lady with St Francis mosaic and initials of the mosaics’ designer and maker.

Two squarish vaulted chapels with their own apses are smothered with the most lavish designs. On the north east corner the Chapel of Our Lady is mostly golden, with scenes from the life of St Francis of Assisi that is filled with plants and birds. Next to that I found the initials of designer and maker - OPUS G.P. & M.J. (above right). On the opposite south east corner of the church is the Chapel of St Catherine, in predominantly deep blue tesserae, with angels flying towards the wheel in the centre of the ceiling (below right).

The Chapel of St Catherine

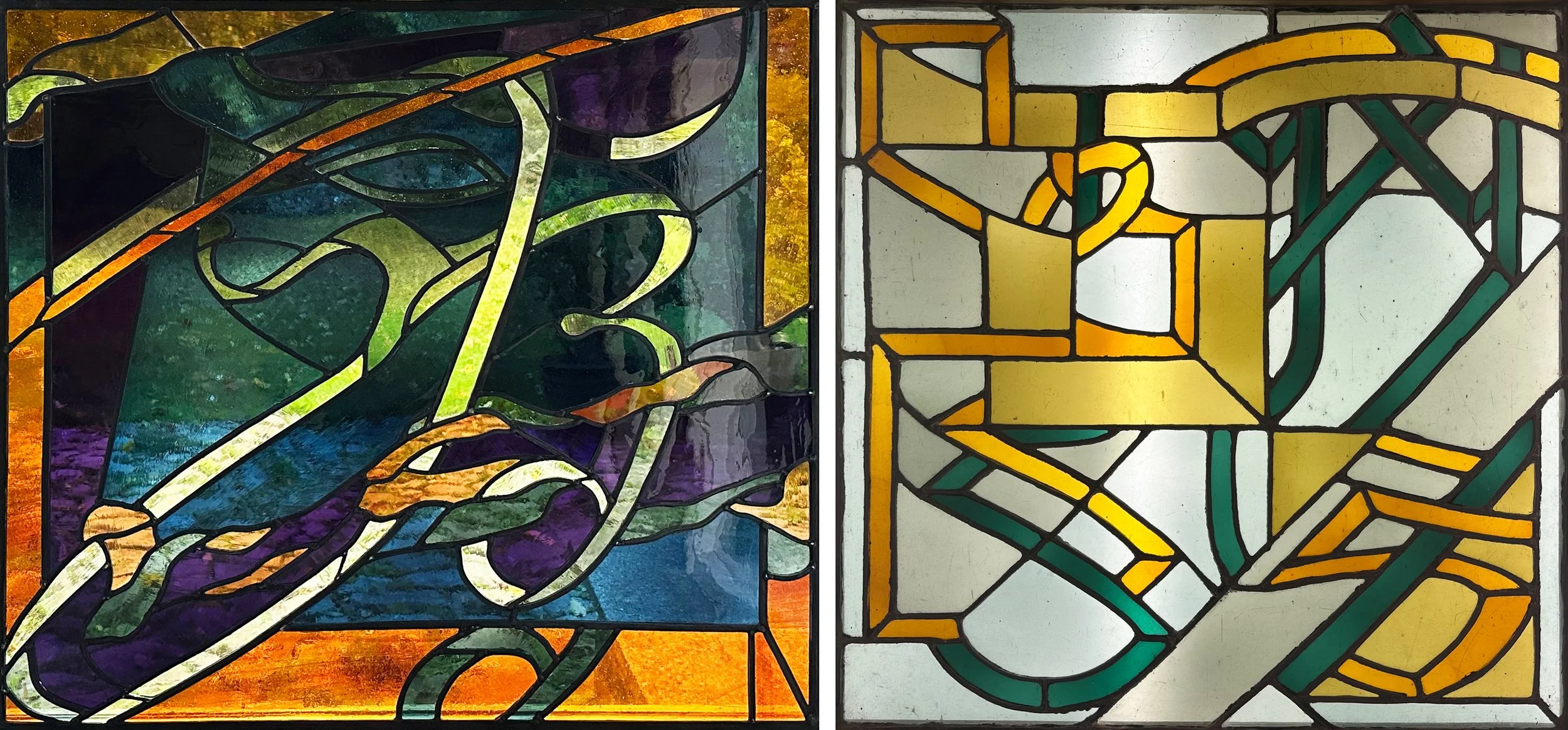

Which brings me to the windows, that are not made of white glass as it appears in the photos where the numerous electric lights are shining on to the walls. They are in fact leaded lights in a lovely range of pale coloured hand blown glass. The ones on the lower level are leaded in a few different scale patterns (below right from St Catherine’s Chapel) while the higher level ones use linked circles. The most ambitious window is on the west wall (below left) surrounded by flying angels above a row of saints. These subtle and satisfying window designs are perfect partners for the mosaic patterns that surround them and extend right into the window reveals.

Left: West Wall with the Nine Choirs of Angels in flight. Right: Window detail from St Catherine’s Chapel.