East Window by Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. 1870, St. Martin's on Brabyn's Brow, Low Marple

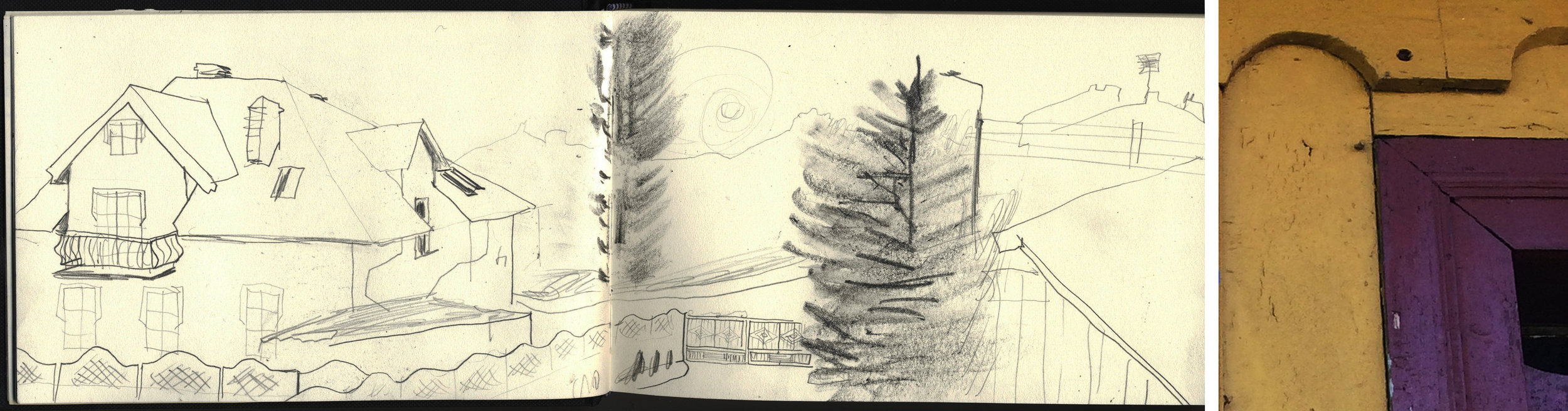

The Church of St. Martin's, Low Marple, near Stockport, was designed and built in 1869 -70 by the Arts and Crafts architect, John Dando Sedding. 'The Firm' (Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.) made three windows for the church; the east window (above), includes figures designed by Burne-Jones, William Morris, Ford Madox Brown and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Visitors come specially to look at this example of a faulty and unrestored window by the firm. As with many windows from this period by a number of stained glass companies, the paintwork quickly deteriorated - came off, not faded as the guidebooks incorrectly say. This defect, caused by using borax in the paint, was something that William Morris corrected by repainting and firing much of the glass in the firm's early windows, but not this one. Here, the appearance of the mostly unpainted glass, with details and patterns removed, reveals the overall design of the window in quite an appealing way.

St. Peter from St. Nicholas Beaudesert (left), from St. Martin's Low Marple (right)

You can learn a lot about stained glass techniques from this window. As you can see in the detail (above right), the silverstain (transparent gold colour) is still there in WM's familiar self portrait as St. Peter although most of the opaque black lines have gone. The comparison with the same figure from Beaudesert also helps.

Since I've started looking at stained glass by Morris & Co. I've had a lot of fun spotting the reappearance of figures throughout their works in tapestry and embroidery as well as stained glass. In this church I found a fourth version of Burne-Jone's Mary, with its paintwork almost intact.

Marys left to right: St. Martin's Low Marple 1873, St. Nicholas Beaudesert 1865, St. Mary's Sopworth 1873, St. Martin-on-the-Hill Scarborough 1868.

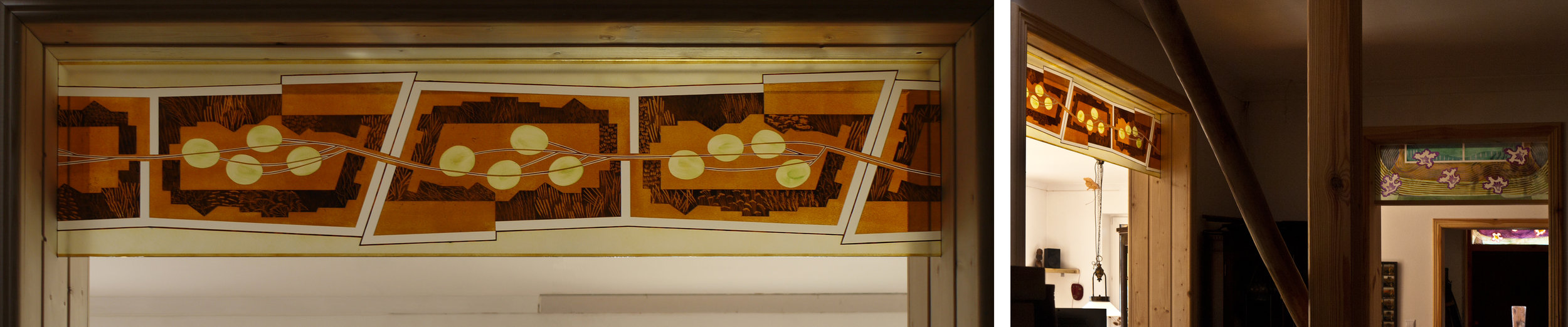

Christopher Whall at Low Marple: The Lady Chapel added in 1895, South West Window 1899, West Window 1892.

The church is also notable for slightly later works by Christopher Whall. The Lady Chapel, with an eccentric 3D ceiling and an altar painting of The Annunciation, is worth going to see. And in his beautiful West Window is a character I had seen and admired recently in Leicester Cathedral (below). It is interesting to compare the differences in colour, background pattern and detail in the two versions of essentially the same figure.

St. Martin from Low Marple (left), from Leicester Cathedral 1907 (right)

I generally identify the stained glass of Christopher Whall by the way he paints people's facial features. The faces of the angels in the great East Window in Leicester Cathedral are typical. When you zoom in on the little people in the boat in the otherwise untypical Whall South West window at Low Marple (below) you can tell that this window is one of his.

Details from Christopher Whall windows, Leicester Cathedral 1920 (left), Low Marple (right)